|  |

By Greg Niemann

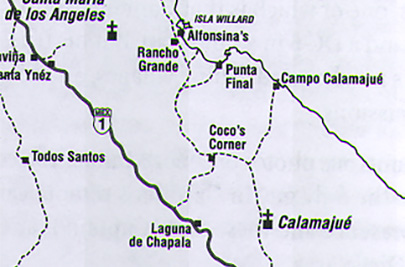

Baja’s long-anticipated eastern connection with the Transpeninsular Highway (Highway 1) is nearing completion. Soon travelers, especially those entering from southeast California and Arizona, will find the new Highway 5 a better option to head into the heart of Baja California.

So far the road is paved from Puertecitos to about 20 kilometers south of Gonzaga Bay, (as of late June 2016) the rest is mostly graded. Today even 2-wheel drive vehicles can make the connection driving slowly. Upon completion, the new paved road from Mexicali to Highway 1 is expected to shave four hours driving time off the old dirt road.

To get the job done this year Mexico has allocated another 290 million Pesos. Project Director Alfonso Padrés Pesqueira stated that the additional federal resources will help get the highway completed during 2016.

Finishing the job is not that simple, however, as five bridges must be built varying from 32 meters in length to the longest at Lake Chapala which will span 108 meters. While additional paved roads open the wilds of Baja to more and more tourists, old-timers know “it wasn’t always that easy.”

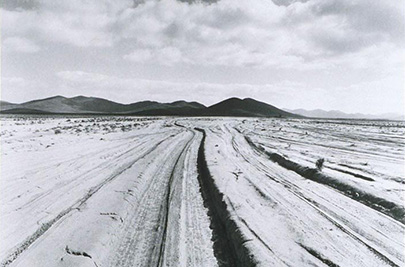

Before 1973 (the year Highway 1 opened), it seemed the only place any speed could be reached was at Laguna Chapala, a dry lake bed in Central Baja California. But the exhilarating ride was short-lived and first earned by traversing a maze of dirt tracks.

The old road entered deep, flour-fine silt, where drivers had created many tracks while trying to find a smoother, less-dusty section. As many as 40 or 50 roads took off in seemingly every direction over a couple of miles, crossing and recrossing each other, and no matter which one you took, you wish you had taken one of the others.

All the roads through the deep powder, however, ended at Rancho Chapala on the edge of the dry lake bed. The historic rancho was founded by a hardy Baja pioneer, Señor Arturo Grosso Peña.

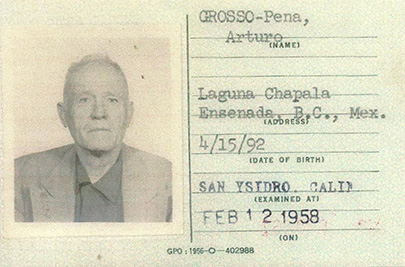

Arturo Grosso, the oldest son of an Italian mining engineer from Santa Rosalia (Eduardo Grosso) and his Indian wife Tecla, became a central Baja legend in his own time. Born in 1892, he was the oldest brother of Señora Anita “Mama” Espinoza, the famous matriarch of El Rosario.

Doña Anita, who had aided Baja travelers for decades and originated the Flying Samaritans, died in March 2016 at the age of 105. (Some reports had her older. She told me she was born on Oct. 16, 1910, the date also listed in the 1985 book Dona Anita of El Rosario. In her own book, Reflections, (1994) she states she was born in 1908 and also erroneously that her brother Arturo was born in 1890. She did mention a lack of accurate record-keeping. Regardless, she lived to well over 100 and, like her brother, inspired thousands.)

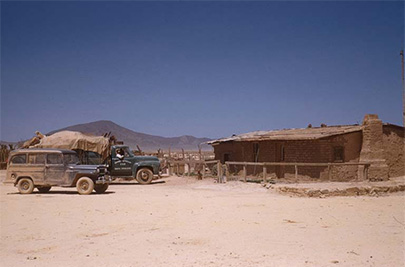

Arturo, who spoke good English like his youngest sister, was also a helpful magnet for adventurous Baja travelers and welcomed all who had entered the broad dry lake area. His modest rancho allowed visitors to camp, offering small guest rooms for just $1 per person, and meals. He even encouraged campers to unroll their sleeping bags on his dining room floor if it was too windy outside. There was a 2,000-foot packed dirt airstrip between the rancho and a nearby hill.

Grosso was a soldier and became known as the person who could get things done. Baja’s Northern Territory Governor Abelardo Rodriguez (later Mexico’s President) turned to Grosso in 1925 for a special project – to build a road for cars through the most impossible terrain of Baja California.

The road would extend from El Rosario in the north to El Arco in the south, a link of about 250 miles. With no engineer or other supervision, “Jefe” Arturo Grosso led a team of only six or seven workers and got the job done in one year. They had a 1924 Ford to shuttle the workers, their tools (rudimentary picks and shovels) supplies, and food. Years later, the paved Highway 1 would be part of or closely follow Grosso’s original work. The building of Baja’s most iconic road is just one story attributed to the indomitable Mr. Grosso.

Erle Stanley Gardner in his 1961 book Hovering Over Baja describes Grosso’s broad influence: “Grosso is an intelligent man, an energetic man, and, according to Baja California standards, a rich man. He has many head of cattle and he has the ability to look and plan ahead. Arturo Grosso is a power. Grosso is friendly, speaks good English and is keenly interested in people and in events.”

There are several stories and photos about Arturo Grosso in the Natural History and Cultural Museum at Bahia de los Angeles, but especially important is another notable and true tale about the illustrious pathfinder. It seems he created another road – the San Felipe-Chapala road, now being morphed into Highway 5.

Baja California became a state in 1952 and was attempting to attract tourists. San Felipe, on the gulf, was just being developed, and in 1955 the state government offered a 10,000 Peso reward (about $800 U.S. at the time) if somebody could create a road from San Felipe south to tie in with the old main road (built by Grosso 30 years previously) near the dry lake bed.

By now in his 60s, Arturo Grosso rose to the challenge. He got some dynamite and blasted a road he could drive his truck through. The road, through Puertecitos and Gonzaga Bay, became known as the “three sisters” for three major summits that challenged adventurers. Driven by many, it was considered one of Baja’s more difficult roads until it was graded in the 1990’s.

But it was a road nonetheless, and it led tourists to the once-secluded Gonzaga Bay area and to connect with the main road south. The rancho at Chapala also became an important rest stop for participants in the early Baja 1000 off-road races.

There are many legends surrounding Grosso; he was so adept at getting things done that it became hard to separate fact from fancy. He was a practical joker and delighted in shocking people – like guests who would ask what they had just eaten. He would take them into the storeroom and point at some dried strips of various game, sometimes with the hair still on it. According to sister Anita, “Any animal that had legs was fair game for Arturo’s stews.

He loved to talk to American visitors in English. He’d drink beer with them and often talk them into a foot race, which the wiry rancher would win almost every time.

Admittedly, he used to help people smuggle illegal parrots into the United States. The smugglers would land at the Chapala airstrip and pay Grosso to water, feed, and care for the parrots while awaiting their journey north. One story he loved to tell was about how once he was shopping on Market Street in San Diego and heard someone say, “Arturo Grosso, Arturo Grosso,” He looked and saw a pet store with two parrots on perches. One said to the other one, “Isn’t that Arturo Grosso from Chapala?” He told the story so many times that even people close to him began to wonder if it could be true.

When the Transpensinular Highway was paved in 1973, the slightly new configuration bypassed Grosso’s Rancho Chapala. No problem. He just moved his rancho – lock, stock and barrel – two kilometers west to the new road.

Grosso and his wife had five children, a son, Eugenio Grosso, and four daughters. In 2001, Eugenio, then 45 years old, his wife Hortencia, and their three children were running the Rancho Chapala. The rancho was still quite rustic, a holdover from a time gone by, but the friendliness of the family lingered. He even let me borrow his dad’s Green Card which I scanned and returned on my next visit months later.

Truck drivers stop for coffee and good basic food. The old wooden rancho walls were decorated with framed jigsaw puzzles, the incongruous lush mountain scenery and European buildings a notable contrast from the desert outside.

Three of Grosso’s daughters had left the arid Laguna Chapala area, but have not migrated far. One moved to Bahia de los Angeles, another to El Rosario, and a third to San Vicente. During the early 1990s, the fourth, Naty, established her own Rancho Laguna Chapala, one kilometer north of the older one.

The original legendary rancher and road-builder, Arturo Grosso died on his 85th birthday, Apr. 15, 1977. All the family members I’ve met throughout Baja, including siblings, nieces, nephews and grandkids, share the pride of their illustrious relative. It was good to learn that the simple life led by this man out in the middle of the driest, most desolate corners of the universe could have such an influence on people.

And remember, whether you drive south into the interior of Baja California on the Transpeninsular Highway 1 or the newly paved Highway 5 – Arturo Grosso was there first!

About Greg

Greg Niemann, a long-time Baja writer, is the author of Baja Fever, Baja Legends, Palm Springs Legends, Las Vegas Legends, and Big Brown: The Untold Story of UPS. Visit www.gregniemann.com.

I had very positive experience buying my Motorcycle Mexico Insurance for my oncoming ride to Cabo...

They are so easy to deal with. They provide great communication. A real sense of comfort while...

Shauna has been super helpful and supportive from day one. Before and after the purchase of the...