|  |

By Greg Niemann

Around the time the United States was being formed, another drama was being played on another part of the North American stage, the area called New Spain, more specifically, Las Californias.

In settling missionary jurisdictional disputes, Spain in 1773 delegated the Baja California missional operations to the Dominican Order of padres. The decree also allowed the Franciscans to settle Alta California, creating an early boundary for what would eventually become two countries.

One major difference would affect the Dominicans. Instead of the Franciscans, and before them the Jesuits, calling the shots, the Dominican Order found themselves subservient to the Spanish crown and military. Another major shift was that previous to the arrival of the Dominicans, there was very little commercial activity between the missions and secular society.

That changed by necessity as the royal treasury was nearly empty and Spain started defaulting on stipends for the operation of the missions. The Dominicans had to learn how to be self-sufficient. They learned to become traders.

As the Franciscans went north in their march to establish missions all the way to the San Francisco Bay area, the Dominicans established their first mission at El Rosario in 1774, the 19th Baja California mission overall.

Spain wanted the next mission to be “a day and a half” up the Pacific Coast. So one year after El Rosario, on or about Aug. 30, 1775, the Dominicans founded the Mission of Santo Domingo some 23 leagues (about 70 miles) north. Padres Manuel Garcia and Miguel Hidalgo, who established the mission, named it for the founder of their Dominican Order of Catholic clergy.

Services Originally in Cave

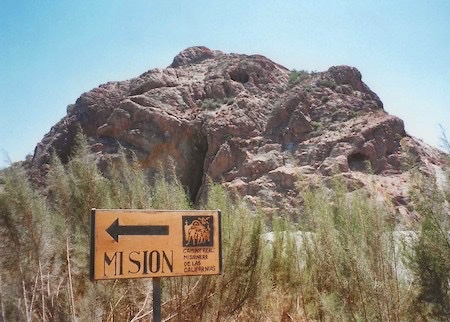

The mission’s first location was in what is now called the Santo Domingo Arroyo near a large red rock that has become a familiar landmark as it is visible for miles. You can still see that rock from Highway 1 about one mile from Colonia Vicente Guerrero, 10 miles north of San Quintín.

Services originally were said to have been held in a large cave in that rock while the mission complex was being built. Now swallows and other birds inhabit the many caves that speckle the huge, round red granite rock that appears as if it had been dropped from space onto the sandy riverbed.

During the summer months however the lower part of the arroyo is mostly dry, so after seven years there by the rock, the mission was relocated four miles upriver in 1782. There 120 acres were put under irrigation, and crops grown for trade as well as consumption.

Santa Domingo was ravaged with smallpox in 1781 which killed about a third of the indigenous population; then later a syphilis epidemic left only 79 locals. For a while the padres had a hard time keeping enough of the population to help harvest the crops. Also many of the locals had been dependent upon fishing from the nearby ocean and thus preferred living by the sea.

Padre traders

An interesting note is that Santo Domingo became a center for the sea otter pelt and salt trade with Russians, conducted at the San Quintìn harbor. The Russians, in turn, traded their Baja California booty with China, the primary market for sea otter pelts. The indigenous locals harvested the otters.

Regarding the San Quintìn sea otter activities, whaler-turned-author Charles Melville Scammon in his 1874 book The Marine Mammals of the Northwestern Coast of North America, mused, “It must have been a strange sight….when Russian sailors, Dominican missionaries, and a sprinkling of Alaskan Aluets assembled on Bahia San Quintìn to instruct the Californians (local indigenous people) on the fine points of capturing sea otters,”

The missionaries had found a good source of necessary income. Of 1,750 pelts sent to China from California in 1787, nearly 1,200 were from the Baja California missions.

Aided by the trade activity, records indicate that by the year 1800 Santo Domingo was healthy and had a population of 257. The livestock included horses, mules, cattle, swine and over 1,000 head of sheep and goats. In that year the harvest of grain was 1,620 Spanish bushels of about 220 pounds each.

The resident missionary of Santo Domingo also served at the visiting chapel of San Telmo, eight leagues (24 miles) northward. San Telmo was a cattle ranch which consisted of a few dwellings, a smithy and a carpentry shop.

Ruins of those buildings have confused some visitors into thinking they were the Mission Santo Domingo. San Telmo is north, off the road to Meling Ranch and the Observatory atop the San Pedro Martìr. Both Santo Domingo and San Telmo closed in 1839 due to more epidemics and finally totally abandoned in 1855.

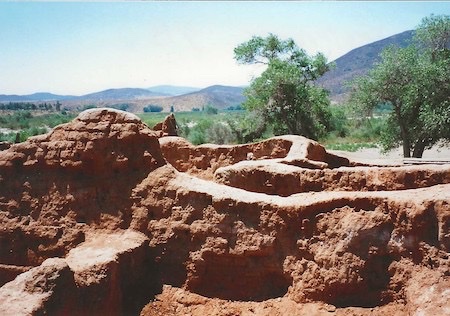

The extensive Santo Domingo mission ruins and foundations, as well as its unusually large cemetery, indicate a considerable population at its peak.

Bells stolen at night

The buildings at Santo Domingo were still intact in the late 1920s, with bells hanging from a crossbeam at the mission’s entrance. The bells were stolen at night in 1930 and the mission began to fall into disrepair.

A visitor in the mid-1900s also observed four three-foot tall and very heavy carved wooden saints in the community. It appears that back in 1855 the mission’s last padre, Father Tomás Mansilla, entrusted the wooden saint statues to the surviving eldest member of the parish, who would pass them on upon his death, thus preserving their safekeeping for the community. Originally there were five, but one had been loaned to a neighboring village for a festival and never returned.

The road from Highway 1 (just north of Colonia Vicente Guerrero) to the mission passes farms with broad fertile fields and scores of colorfully attired pickers, mostly indigenous to the fertile San Quintìn Valley. Multi-hued, brilliant bandanas hold their hair in place as they stoop in the morning fog to quickly and deftly harvest the abundance of tomatoes and chilies the area now provides.

Past the bright red rock the arroyo narrows and a small settlement of houses abuts the old mission ruins. A sign announces the two and a half century old mission, of which many walls are still standing.

Arthur W. North, the author of The Mother of California and Camp and Camino in Lower California, was seemingly the first American to visit most of Baja’s missions in the early 1900s. Of Mission Santo Domingo, he reported that it was the best preserved of the Dominican missions.

Visitors in the mid twentieth-century found this to be still true. In 1949, authors Marquis McDonald and Glenn Oster visited the site by jeep. They reported that nearly all of the walls were still standing and some of the window and door apertures were still intact.

In 1989 I found continued weathering, yet the outline of the entire compound was still visible and many walls were standing. A large wooden door beam still stood, supporting two feet of adobe. Windows and doorways were still evident, providing framing for the weathered walls which once housed a thriving community. The site is still well preserved.

Driving back out to the highway, I again looked up at the red monolith standing like a sentinel to the arroyo. I thought that while the later mission’s adobe walls continue to crumble through the years, the padres’ first mission site, that large rock, should stand for millennia.

And the sea otters? They were hunted to almost extinction, and by 1910 were approximately only 1,000 left worldwide. They were declared extinct in 1969. Due to conservation efforts, it is estimated that there are about 3,000 southern sea otters in the wild today. Today there are still sporadic sightings in the San Quintìn area.

How to get there:

Highway 1, 102 miles south of Ensenada, 7 miles south of Camalu, on the north bank of the bridge crossing Rio Santo Domingo is a dirt road with a sign marked “mission.” Follow the road to red rock and continue up the canyon. About 5 miles from the highway.

About Greg

Greg Niemann, a long-time Baja writer, is the author of Baja Fever, Baja Legends, Palm Springs Legends, Las Vegas Legends, and Big Brown: The Untold Story of UPS. Visit www.gregniemann.com.

In a somewhat unusual accident, BajaBound (Ms. Garcia/Mrs. Lopez) and HDI (Ms. Villalpando) were...

I have used Baja Bound for years. Very easy and affordable.

Very easy to buy a insurance plan