|  |

By Greg Niemann

The Mexican Revolution that began in 1910 spawned many changes for that country. Along with radical political upheaval, there were also stories of heroism and defeat, and of hope, despair and opportunism that emerged from the multi-faceted revolution.

One of the most curious stories was when, ostensibly under the banner of the overall revolution, an organized group of socialists invaded Baja California.

In 1911, a year after Francisco I. Madero began leading his “Maderist” army against Mexican President Porfirio Diaz, socialists decided to get into the fray and chose to act in the state of Baja California.

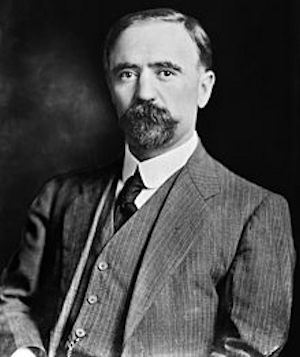

While the Baja uprising took the appearance of being part of the overall Mexican Revolution, it was actually a specific socialist revolution engineered by Ricardo Flores Magón, a long-time enemy of the Diaz dictatorship.

Born in Oaxaca in 1873, Ricardo Flores Magón had fought the Diaz dictatorship in every way, going back to when he was a Mexico City law student. His street demonstrations and dissident writings landed him in prison, but did not deter him. President Diaz controlled the media, so in 1904 Ricardo and his brother Enrique Flores Magón went to the United States and continued their diatribe, running the operation from Los Angeles.

Mexican Liberal Party

After Diaz placed a price on their heads, they even fled to Canada for a while. Later back in Los Angeles, they were able to control their revolutionary activities under the auspices of the Mexican Liberal Party.

In 1908 all the leaders were arrested while crossing into Mexico to begin an insurrection and jailed again. When they were released from this incarceration, they were able to loosely align their cause with the insurgent Maderist revolutionaries.

But the Magonistas, as the brothers’ liberal movement became known, wanted not only to topple the men in power, but the entire economic structure. They were true socialists and wanted total distribution of land and wealth.

With Baja California so physically close to the Los Angeles base of Magonista activities, that state became the focus of their attention. They were well financed with money from liberal American sympathizers. They attracted the support of liberal workers and some U.S. labor groups, including the most radical and militant of all, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), also called Wobblies.

When the Mexican Revolution broke out in 1910, the Mexican Liberal Party was prepared and carried out its own, more economic revolution. There were no Maderists fighting in Baja California, so it was up to the Magonistas to take the insurrection there.

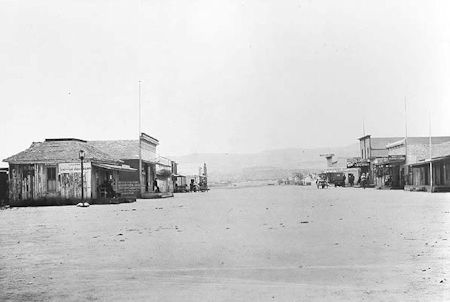

In the early morning hours of Jan. 28, 1911, a handful of men were sent by the Magonistas to Mexicali, then a village of about 400 people. They killed the jailer and released the prisoners, including two liberals. The town’s leaders either surrendered, paid cash for their liberty, or fled.

Soon the Mexican Federalist army took off after the by-then reinforced rebels. There were a few skirmishes, a few deaths on both sides, and two bridges near Mexicali were destroyed. The Americans watched with interest and by March 7 had 30,000 troops lined up along the border, standing by for possible intervention in another country’s civil matters.

On March 12, the border town of Tecate fell to a handful of socialists, led by a member of the Wobblies.

A Soldier of Fortune

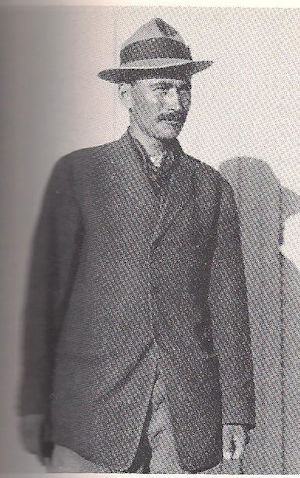

The rebel forces were soon composed principally of foreigners either sympathetic to the cause, like the Wobblies, or soldiers of fortune like the Welshman Caryl Ap Rhys Pryce, who led an attack on Tijuana. His week-long march culminated in a hard fought battle on the morning of May 9, 1911, during which the town fell to his invading liberals. Of course, to the victors went the spoils and much looting occurred.

Pryce didn’t stop with looting. He began collecting taxes, licenses and customs fees, generating revenue for the Magonistas. He even had the audacity to open the city of Tijuana to tourism, charging 25 cents per visitor, further enhancing the coffers.

Ricardo Flores Magón had Pryce begin planning to attack the town of Ensenada, but that attack never happened.

After the Madero government toppled Diaz and requested the Magonistas to disband, the Magón brothers refused and wanted to continue the struggle. Not driven by idealism, Pryce was infuriated by their persistence and quit the movement.

Pryce promptly disappeared, taking with him those funds collected. He was later arrested in Los Angeles, but was successful in an extradition hearing which would have sent him back to Mexico on murder and neutrality charges. The adventurer then was a successful movie cowboy before joining the Canadian Army when WWI broke out. He served with honor and retired with the rank of Major.

The departure of Pryce in Baja left a fellow named John R. (Jack) Mosby in charge. The new rebel commander had a dubious past which included deserting from the U.S. Marine Corps and becoming an IWW member in Oakland, CA. But by then, the socialist revolution of the brothers Flores Magón and their supporters was at a standstill.

In the confusion, a Los Angeles self-promoter named Dick Ferris stepped in. A promoter, publicity man, dreamer, and a bit of a clown, Ferris was responsible for the publicity of the Panama-California Exposition in San Diego to commemorate the opening of the canal. Another rebel with an interesting past, he had previously tried to blackmail President Diaz into selling the Baja California peninsula.

After he stormed into Tijuana with reporters in tow, he tried to establish Baja California as an independent republic, in the manner of William Walker and numerous other filibusterers in the late 1800s. The press linked him with the revolution. However, Mosby, who was now in charge of the Flores Magón socialist forces, denounced Ferris as one who had absolutely nothing to do with the revolutionary movement.

But Ferris played up the publicity he generated and later became a successful actor playing “The Man From Mexico” to packed houses. A man of many interests, he helped organize the Los Angeles Yellow Taxi Cab service. He also leased 14,000 acres of land between Tijuana and Ensenada to establish what was to be called the Paradise Beach Club. He died in 1933.

Zealots to the end

In 1912 Mexico’s new President Madero wanted to make peace with the Junta of the Liberal Party (meaning Flores Magón) and tried to convince Ricardo and Enrique to join him. He even sent their oldest brother, licencio Jesus Flores Magón, to Los Angeles as part of the peace emissary. They emphatically rejected all offers.

While peace talks were going on, Federal forces attacked Tijuana, taking control of the town and throwing the rebels out. Out of about 500 insurgents in town at the time, 31 were killed and many wounded. Mosby escaped across the border, but was later arrested and sentenced (for desertion from the marines). On the way to the penitentiary he was killed while trying to escape.

While the losses at Tijuana signaled the end of the Magonista movement, the zealot Ricardo Flores Magón refused to recognize it and continued to fight for social upheaval.

On June 14, 1912, he and his small band of core followers were arrested in Los Angeles and sentenced to the maximum 23 months in prison. Upon appeal, in 1913 U.S. President Woodrow Wilson himself wrote to California Congressman John P. Nolan, “I took up and examined very thoroughly the case of Ricardo Flores Magón…, and I am sorry to say, that after looking into the case as fully as possible, I am convinced that it would not be wise or right to grant a pardon.”

Never relinquishing his beliefs, Ricardo Flores Magón spent a total of 10 years in prison during the time when he had fled to the U.S. shortly after the turn of the century until he died in his prison cell in November 1922.

The idealists and adventurers who tried to bring a socialist upheaval to Baja California are now relegated to history books, adding their names to the many who tried to change or “conquer” Baja through the years.

About Greg

Greg Niemann is the author of Baja Fever, Baja Legends, Palm Springs Legends, Las Vegas Legends, and Big Brown: The Untold Story of UPS. Visit Greg's website.

2nd time I have used this company,, first class service and great price.

Baja Bound makes insurance for my occasional weekend motorcycle trips to Mexico easy and...

I had very positive experience buying my Motorcycle Mexico Insurance for my oncoming ride to Cabo...