|  |

By David Kier

Perhaps one of the most impressive of the Spanish structures on the peninsula is the massive stone church in San Ignacio. Let us review how Mission San Ignacio was established over three hundred years ago and when the grand church was constructed.

In November of 1716, while exploring out from his mission at Mulegé, Padre Francisco María Píccolo was shown a miracle. In the center of the peninsula, a river of fresh water emerges from under a lava flow! Píccolo had been informed about the place some months earlier. That is when the Jesuit priest sent one of his catechists to investigate. He was a Christian Cochimí man named Joseph who upon arriving at this river offered salvation for three sick infants.

Six days after leaving Mulegé, making stops along the way at Cochimí rancherías (villages), Píccolo arrived. The people had invited him to examine the place and see their river. They were hoping he would establish a mission for them. The Cochimí called the place Kadakaamán (Sedge brook). Padre Píccolo gave it a Christian name, calling it Río San Vicente.

The three rancherías along this river were soon joined by members of eighteen others. Píccolo, with his soldiers plus two Christian boys from Mulegé, handed out gifts, corn, and chocolate. The Jesuit said Mass on November 19, 1716, in a small shelter they had erected. Píccolo assigned a man named Yetchui to be an official representative in the interim until the Jesuits returned.

Padre Píccolo was back at Mission Santa Rosalía de Mulegé on December 6, 1716. He immediately wrote to his superiors in Mexico about the potential of this new location and the eagerness of its people for a new mission to be founded there.

In 1718, Padre Sebastián de Sistiaga replaced Padre Píccolo at Mulegé. Over the next ten years, Padre Sistiaga traveled to the future mission site frequently and provided instruction.

In 1720, the Mission Guadalupe de Huasinapí was founded in the mountains west of Mulegé. Its founder, Padre Everado Hellen, joined with Sistiaga to help at Río San Vicente as no other place on the peninsula had such an abundant supply of fresh water, with numerous friendly Californians.

In 1724, a young Jesuit student named Juan Bautista Luyando, coming from a wealthy family, had endowed the future mission with funds from his own inheritance. The future mission was to be called San Ignacio, the patron saint of Luyando as well as being the founder of the Jesuit Order: San Ignacio de Loyola. In 1727, with his schooling completed, Luyando came to California and learned the Cochimí language with Padre Sebastián de Sistiaga.

Padre Luyando, along with Padre Sistiaga, nine soldiers, and a long pack train of supplies, arrived on January 20, 1728, to establish Mission San Ignacio de Kadakaamán. Work began at building huts for the Spanish men and a larger shelter to serve as a chapel. Agriculture was of upmost importance to provide adequate food for the neophytes of the new mission. Canals were built to bring water to the new fields. Figs, grapes, pomegranates, and sugar cane were planted. Later, those crops were followed by the addition of wheat and cotton.

Construction even began on an adobe church to replace the one made of sticks and reeds. After several days, Padre Sistiaga returned to his mission at Mulegé while Luyando continued on at San Ignacio. Over the next five years, these two often were recorded serving at the other’s mission, or at Mission Guadalupe.

The Jesuits were building a very prosperous mission with multitudes of Cochimí coming for conversion. Roads were built out from San Ignacio to make for better communication with the pueblos de visita (satellite villages of the head mission). There were few Jesuits available to manage all the missions at any one time, Padre Luyando also assisted at Mission Guadalupe and Mulegé when their own priests were either ill or called away to serve elsewhere.

Juan Bautista Luyando labored greatly at San Ignacio but was not in the best of shape physically. By 1733, he retired to Mexico after having been replaced by Sigusmundo Taraval, the Jesuit from Mission La Purísima. Padre Sistiaga continued dividing his time between Mulegé and San Ignacio. Taraval would soon be assigned to the Todos Santos mission, Santa Rosa de las Palmas. This was as soon as the next Jesuit arrived at San Ignacio. This next Jesuit was Fernando Consag, who labored there and performed other duties from 1733 to 1759. More about Padre Consag in this article.

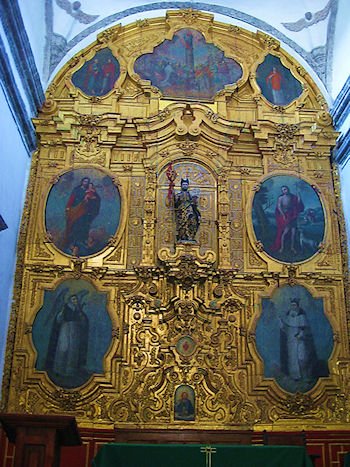

Some say Fernando Consag began the construction of the massive stone church, but most give that honor to San Ignacio’s next missionary, José Rotea in 1761. Padre Rotea is also credited for building the massive stone and earth flood control dike named La Muralla.

Work on the giant stone church was interrupted at the end of 1767, when all sixteen of the Jesuits in California were ordered to Loreto. There, they would be taken away, ending the Jesuit Order’s seventy years on the peninsula. This action was based on lies and false information from rumors that the priests were disloyal to the King and hoarding treasures.

The Franciscans, led by Junípero Serra, arrived in April of 1768 to occupy the Jesuit founded missions of California. A year later, they were instructed to expand the California missions beyond the last one at Santa María, going on to San Diego and Monterey. On this expedition, they founded their only Baja California mission at Velicatá, calling it San Fernando. In 1773, the Franciscans would hand over the peninsula to the Dominican Order. The Franciscans could now put more effort into the Alta California mission program.

The new Dominican padres were excited to have this region where they could continue the conversion of the Natives and build more missions in the wide gap between San Fernando and San Diego. It was the Dominicans, led by Padre Juan Crisóstomo Gómez, who completed the giant mission church at San Ignacio, in 1786.

In 1822, after the defeat of Spain, Californians pledged allegiance to Mexico’s new government. The period of the Spanish missions had ended. Some Dominicans left their missions and returned to Europe. A few Dominicans were devoted to their churches and stayed. Mexico allowed missions to operate until they were abandoned or until the death of their priest. The need for Native instruction was still considered essential in Baja California.

The year 1840 was the final year for Mission San Ignacio with the mysterious death of Padre Félix Caballero. Continue reading about of this dynamic time in history. Find more in my book, Baja California Land of Missions.

Very clean, well kept/landscaped/maintained property. Excellent food, drink as well as friendly...

Fair price. Webpage could be improved.

Check them out - best place to get Mexican Insurance before you leave for your trip/vacation