|  |

By Greg Niemann

Certain old ranches have become part of Baja California folklore, especially those that had small airstrips and catered to Americans in the 1950s and ‘60s. As the primitive roads of Baja were used only by the hardiest adventurers, air guests could literally drop in at remote locations for fishing, hunting or relaxing.

There were several such hideaways, including Meling Ranch, Mike’s Sky Ranch, Johnson Ranch (San Antonio), Santa Maria Sky Ranch, Santa Ynez, and farther south, the Serenidad in Mulegé and the Flying Sportsman in Loreto.

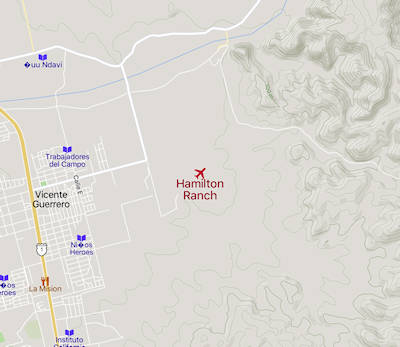

There was also the Hamilton Ranch, in an agricultural area about three miles in from the main road near Colonia Guerrero, north of San Quintín. It was primarily reached by the accompanying airstrip for medium-sized planes. There is an alternative route off the Santo Domingo Mission road that crosses the arroyo by the big red rock which is still a scenic backdrop to the ranch.

A 1966 Auto Club guidebook noted that the ranch offered 11 rooms at $10 per person, including meals. The book also mentioned good fishing nearby, and deer, quail, duck and geese hunting in the area.

Author Erle Stanley Gardner whose pilot Francisco Munoz landed many times at Hamilton Ranch, refers to it several times in his books, including this passage from 1961’s Hovering Over Baja: “Margo Ceseña, who operates the Hattie Hamilton Ranch, is a remarkable character. Tall, vital, competent, freedom-loving and independent, she operates the ranch just as much by herself as is physically possible....Margo is a colorful character and it is well worth a trip to the Hamilton Ranch simply to visit with her and hear her cheerful laugh....”

An 1845 Land Grant

The ranch was originally part of an 1845 land grant to Jose Luciano Espinosa. He received one sitio, (4,338 acres) of what was then called the San Ramon Rancho and was also granted the neighboring Santo Domingo Rancho (one sitio), where the 1775 Dominican mission was established.

From its mid-19th century opening to the 1970s, the ranch became a landmark for Baja travelers.

By 1861 Rancho San Ramon had a population of three men, three women, five children, and 40 cattle, and by 1867 they were also raising fine horses. Espinosa died in 1869 at his Santo Domingo Rancho, and his widow, Maria Rosario de Espinosa, died in 1897.

The San Ramon Rancho was then owned by Señor Richard Stephens who had worked as a civil engineer with the International Company, a British firm which had been busy colonizing the San Quintín area.

San Ramon Rancho later became the Randall Young Ranch. Young was one of the original English colonists lured to the San Quintín valley by the International Company in the early 1890s.

Young worked the ranch and made it profitable. Soon fruit and high-quality vegetables flourished, and the Young Ranch became the major produce supplier for the entire San Quintín Valley.

Randall Young died in 1920 and left the ranch to his niece Harriet “Hattie” Hamilton, who was born in England in 1875 and was still in her teens when she arrived in Baja with her uncle.

Young was buried on the ranch and an onyx cross built by mining engineer George Brown, (manager of El Marmol onyx mine) was placed on his grave. The Browns were frequent ranch visitors.

Brown’s daughter, Margaret Brown Baldwin, born in 1890, had spent much of her early life in Baja California and in 1975 she reflected:

“Hattie Hamilton’s was a cool welcoming oasis. It lay in the valley of Santo Domingo River and at times the river was so full one could not get across with an auto and then the mules from the ranch pulled us over.

“Hattie was a wonderful hostess. She had come from England over seventy years ago as a young girl to be with her uncle. There were several acres of every kind of fruit-bearing tree that would grow in the locality, a vegetable garden, flowers, many chickens, and cows.”

Hattie began to take in paying guests and offered 11 inexpensive guest rooms situated around a central courtyard. The ranch became known for good meals and pleasant hospitality. As is sometimes found in isolated locations, the Hamilton Ranch bar was set up on the honor system—you just wrote down what you drank and settled up when you left.

By this time American outdoorsmen had discovered the area for nearby fishing and hunting. It soon became a local base for quail, geese (Black Brant), duck, and other small game hunting. It also offered forays into the Sierra San Pedro Martír to the east for deer, mountain lion and bighorn. Fishing from the Bahia San Quintin became attractive, offering anglers an abundance of species, including rockfish and feisty yellowtail.

A 168-foot runway was built adjacent to the resort and sportsmen began flying in; tourism began to supplement and exceed the farming business. Soon, along with the aforementioned author Gardner, other notable Americans also discovered Hamilton Ranch and flew in for respites.

In 1927 The Automobile Club of Southern California, which had begun mapping and reporting on Baja California, extolled the amenities of the Hamilton Ranch: “It surely is a surprise to find these modern conveniences in this out of the way place.”

Before the airstrip was built, Gardner had visited Hamilton Ranch by land. In his 1948 book The Land of Shorter Shadows, he says, “When I first made the trip some 15 years ago, it was rather a trying ordeal. The roads held the motorist to an average speed of ten miles an hour. Now it is only a three or four hour run from Ensenada....”

In that same 1948 book, he lamented that the ranch’s “guiding spirit” Hattie had sold out “just a short time ago.”

Margo Ceseña continued hospitality

It was purchased by Ray Parodi and his wife Margo Ceseña, and, according to all reports at the time, continued Hamilton Ranch in Hattie’s friendly tradition of welcoming sportsmen as it had in the past.

In 1949, when Marquis McDonald and Glenn Oster traveled through the area researching their book Baja: Land of Lost Missions, McDonald reported: “At Colonia Guerrero, we turned east, passing the well-known Hamilton Guest Ranch. Like the Meling Ranch, but better known, this is a favorite resort of wealthy California sportsmen, and we saw the parking lot filled with large cars. There were also several small planes at the small private landing field.”

One visitor to Hamilton Ranch during the 1940’s was Dr. Carl O. Sauer, “the dean of American historical geography.” He was instrumental in the development of the geography graduate school at U.C. Berkeley, and with interests in Indian and Mexican cultures, he often traveled to Baja.

Dr. Sauer regularly stopped off at Hamilton Ranch with small groups of grad students, many of whom later wrote of their research in Baja California. Some of the students also wrote of their positive experiences, warm welcome, and good meals at Hamilton Ranch.

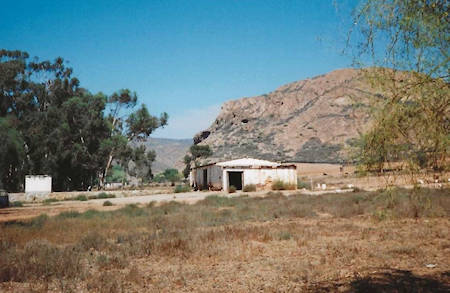

I’d read so much about this place I had to find it. So back in the year 2000 I did just that. After a few initial wrong turns in my Ford Explorer, as I neared the site it became easy to spot, with its numerous wooden buildings in a grove of eucalyptus trees. The ranch house dwellings rest on a high spot on the south flank of the big red rock that was the first location of the Santo Domingo Mission. Farmland spreads out on three sides below the ranch.

As I approached, the abandoned setting appeared more and more ominous. A fine layer of dust billowed about as I came to a stop. I heard and saw a generator running but could not roust a human. The entire place was in disrepair. A worn, weather-beaten old ranch house seemed held together by the rock chimney from which it had become partially separated. Furniture, books and household items from a half-century past lay about the rotting wooden floors, a fine layer of dust covering it all. A couple of old cars lay rusting outside.

The guest rooms, now boarded and empty, that once faced a compact courtyard, were today overrun by weeds. The entire place looked as if its occupants just walked away many years ago and never came back. Inside the main house, near the back door I could see books on the floor, books in English helping to validate that this was indeed the Hamilton Ranch. I would have loved to have had the time and the permission to search the premises, but just respectfully peered in the windows.

Out back, while I never spotted an onyx cross, I found one grave, prominent and well-marked. It was that of Margarita Ceseña, born in 1907, interred in 1987. That would have been Margo, whose cheerful laugh once delighted a famous author.

A few of the legendary old ranchos that welcomed Baja’s early visitors have survived through the years. Many, like Hamilton Ranch, did not. The grand old place had once served as a vital link, bridging a desolate, remote Baja of yesteryear with the tourist developments of today’s Baja California.

About Greg

Greg Niemann, a long-time Baja writer, is the author of Baja Fever, Baja Legends, Palm Springs Legends, Las Vegas Legends, and Big Brown: The Untold Story of UPS. Visit www.gregniemann.com.

Until you have a claim can one truly rate an insurance company. Reasons for 5 star is for two...

Baja is the best. Canadians, we insure our boat and car online through them 2 years now. Easy to...

Easy to understand and great customer service. Emailed Michelle with some concerns I had about a...