|  |

By David Kier

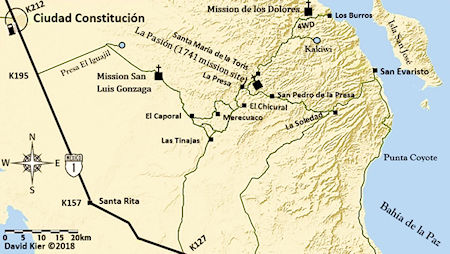

The Dolores mission story is one complicated enough to cause both interest and confusion with the Baja Bound traveler or researcher. Ruins can be found at two locations that are fifteen miles apart. The mission of Los Dolores might be a bit of a mystery to Baja California travelers. It is not near a major road and the ruins at the first site can only be seen from either a distant cliff or by taking a long and steep hike on the mission trail, El Camino Real. Maps do show a long 4x4 road coming south along the coast from Timbabichi, however, its current condition is questionable.

The original site for Nuestra Señora de los Dolores was seen by the Jesuit Padre Clemente Guillén during the 1720 overland trip from his mission, San Juan Bautista de Malibat (originally, de Ligüí). Guillén and company went to help open the new mission at La Paz. During this long journey, a promising new mission location was observed. Water was found near the gulf shore but tasted salty. One league (~2.5 miles) inland, fresh water flowed out of the canyon and Guillén noticed land that could be brought under cultivation. This watered place had been discovered by the pearl divers of a century before. The Native Guaycuras called this place Apaté.

The Ligüí / Malibat mission location had many problems, including lack of water and attacks from the Pericú Natives, who lived on nearby islands. Also, the benefactor, Juan Bautista López, went bankrupt and the funding was lost. Read more about Ligüí history.

On August 2, 1721, Padre Guillén closed that mission and moved south to Apaté. A new benefactor, the Marqués de Villapuente, made establishing a new mission location possible. The new mission name was Nuestra Señora de los Dolores (Our Lady of Sorrows). Because of a visita of the Loreto mission that was named Dolores, ‘del Sur’ was typically added to this new mission’s name for clarity. (A visita is a mission visiting station or satellite chapel, at a Native settlement, which is visited by the padre.)

Services and early mission activities may have occurred near the beach (today’s Rancho Los Dolores) but within two years, building of a church, dam, aqueduct, and reservoir was underway. A nearby cave was modified into a storage room, as well. Mortared stone walls, from the mission church, still stand three hundred years later.

Padre Guillén had desired to relocate the mission out of the box canyon to one of its visitas as early as 1734. This would help him serve a greater number of the Guaycura people. However, the Pericú Revolt broke out that year, south of Los Dolores. The rebellion caused the destruction of the four southernmost missions (Santiago, San José del Cabo, Santa Rosa, and Pilar de la Paz). This made Dolores, as the closest mission, a base for military operations to regain control of the south. By the end of 1736, the Spanish regained control but the loss of two Jesuits padres, and countless innocent and waring Pericú, was difficult to recover from.

Mission Los Dolores had several pueblos de visita (chapels the Padre would visit on rotation at Native settlements). Two of these visitas became missions in time: San Luis Gonzaga and La Pasión del Señor. San Luis Gonzaga was elevated to a mission in 1737 and La Pasión became a mission in 1741 when Los Dolores moved there from Apaté. This final Dolores mission site was fifteen miles distant and known by the Natives as Tañuetía (The Place of Ducks) and later known as Chillá. After the move, Mission Los Dolores was usually called La Pasión by the Jesuits. Perhaps this was to be clear about which location they were speaking about. This had caused some history writers in the Twentieth Century to believe these were two different missions, a common issue with other missions that moved and then used other names (Pilar de la Paz to Todos Santos, Calamajué to Santa María, and San Miguel to Descanso).

In a 1745 Jesuit report, we read that Padre Clemente Guillén had established the following five visitas: La Concepción, La Encarnación de El Verbo, La Santisima Trinidad, La Redempción, and La Resurreción. By the year 1747, old age and illness forced Padre Guillén to retire to Loreto. Lamberto Hostell had previously stepped in to assist Guillén from 1741 to 1743 and again in 1746 until the end of the Jesuit period the following year.

In 1759, the Jesuit’s supply ship was lost off of Cabo San Lucas when the crew attacked their captain, killing him. They then destroyed the ship to fabricate a story that a storm sank it, that their captain was a poor swimmer and did not survive. This loss was especially hard on Padre Hostell who could now only depend on overland delivery of supplies using the difficult road from Loreto.

Don Gaspar de Portolá was appointed governor of California after Spain decided to remove the Jesuits, following rumors of their hording wealth, and not sharing with the King. The Jesuit Order had been falling out of favor with the European monarchies for the previous years and replacing them had already begun in other regions of the New World. Any excuse was enough for the Spanish Crown to terminate the Jesuits control in California.

Portolá attempted to cross the violent Gulf of California twice before, but succeeded on his third time, in October 1767. The crossing took him and the fifty soldiers forty-four days. Rather than arriving at Loreto as planned, winds pushed the ship south to San José del Cabo. At that time, it was a visita of Mission Santiago. Governor Portolá set foot on California soil near the end of November. From there, he would travel overland to Loreto, keeping secret his orders from the Jesuits he met along the way. Padre Ignacio Tirsch of Santiago came south to greet Portolá and accompany him back to his mission.

Ten days after leaving Mission Santiago, Portolá arrived at La Pasión (Mission Los Dolores) where he found a settlement consisting of a cluster of adobe huts and a ‘properly maintained’ chapel. Ten more days travel brought Portolá to Loreto, on December 17, 1767.

In the final week of 1767, the California Jesuits learned their fate would mean seventy years of effort, building communities, and the founding of seventeen mission centers, was over. Spain took over civil duties as the Jesuits’ authority in California was terminated. All sixteen Jesuits were removed from California. In reality, the Jesuits were aware of future changes and welcomed the idea of either getting help with or handing over their missions to the Franciscans. Spain anticipated resistance by the California Jesuits and treated them as criminals. This was something that was not at all necessary.

The Franciscans arrived in (Baja) California in April 1768 to assume mission duties and appointed Padre Francisco Gómez to serve at Los Dolores (La Pasión). No longer were the Native lands or languages respected. The Californians were now seen purely as subjects of the King of Spain. The new person of authority was Visitador General José de Gálvez and in September 1768, he ordered Mission Los Dolores closed. The 458 Guaycuras from Mission Los Dolores were relocated to Todos Santos, where the land was more productive. Being far removed from their ancestral homeland and the loss of the Jesuit padres they had followed for so many years was devastating to the Guaycura Natives. A mission of sorrows, indeed.

To see the 1741 La Pasión site, a pickup or SUV is recommended. Maps now show Rancho La Capilla there. This goat ranch has a new campground called Cabañas La Pasión, with a Facebook page. Find it between Rancho La Presa and Santa María de la Toris, across the big arroyo from the graded road between the above two places. Foundation stones and rubble from the stone walls of the mission are behind the ranch house and above the camping area. Rancho La Capilla (La Pasión) is thirty miles from Mission San Luis Gonzaga and fifty-two miles from Highway 1 at Km. 195, south of Ciudad Constitución. There are also other ways in. GPS: N24° 53.27’, W111° 01.86’. The Amador family will show you many historic features on their ranch and nearby.

To visit Los Dolores Apaté (4WD recommended), go fifteen miles past the Los Dolores Chillá (La Pasión) mission site and hike down the Jesuit trail to the canyon floor from here: N25° 02.37’, W110° 54.58’ or go two additional miles and walk over to the cliff edge to look down on the mission site: N25° 03.33’, W110° 53.06’. Another option is to arrive by boat and hike just over two miles up the canyon. Maps show a possible road coming down the coast from Timbabichi, but I have no information on its condition.

***Please note that some of the roads featured in this article are not conventional roads and our insurance coverage would not apply. Our coverage is only valid on paved and dirt roads designed for the normal transit of vehicles.

Getting my insurance online was easy. I’ll use them again.

Easy process to obtain insurance for my trip. The company reminded me a week before the trip to...

I received service above and beyond my expectations from Angela at Baja Bound Mexican Insurance...