|  |

By Greg Niemann

They’re considered the finest examples of cave art in the Western Hemisphere. Yet the centuries-old paintings in Baja California have been available to westerners only for the past half-century or so. It wasn’t until several explorers, writers and adventurers documented and analyzed these significant finds before the public learned much about them.

Writer Erle Stanley Gardner visited numerous caves in the early sixties and later brought in archeologists to document the incredible discoveries. (The Hidden Heart of Baja, Erle Stanley Gardner, Jarrolds Publishers, 1962). In the 1970s author Harry Crosby explored numerous areas in Baja’s central mountains by mule and pack burros documenting and photographing over 200 sites. His resulting book remains a very comprehensive study on the paintings. (The Cave Paintings of Baja California, Harry W. Crosby, Sunbelt Publications, 1997).

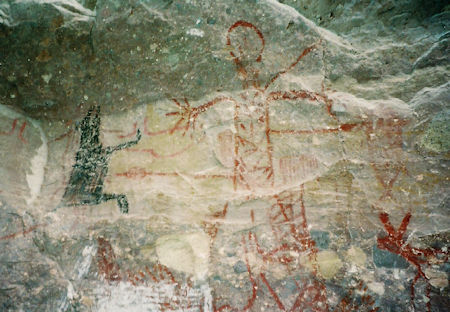

Central Baja California abounds in remote mountain sites where predecessors to the indigenous Cochimi Indians used sheer mountain cliffs as their palettes. There, applying inky substances from plants in black, red and ochre ink, they gave us clues of their existence. They drew the animals they hunted, the arrows they crafted, and the victorious celebrations.

Visiting many of these mountain art sites requires considerable effort while some are easier to access. The most picturesque caves, including what is considered the grandest, the Cueva Pintada (Painted Cave, also called Gardner Cave) or the Cueva Flecha (Arrow Cave) require a journey of several days down into steep canyons on the backs of sure-footed mules.

Cataviña

In the late 1990s and early 2000s I visited several art sites, including the easily accessed one in the Cataviña area. Less than a mile north on Highway 1 from the Hotel Mision Cataviña the highway fords a stream. The first time I visited this little gem of a cave I hiked from that junction, but it’s easier to drive north up the hill to the first clearing where you can pull off the highway.

Drive in and continue to the base of a hill overlooking the junction of two streams. Looking up you should see a sign announcing the small cave.

There’s a short scramble up a trail and the cave is actually formed by large boulders. It’s not much, just a crawl space, a kind of boy’s hideout actually. But there are some colorful paintings on the ceiling, a sunray and a few circles and other markings. But for accessibility, you can’t beat it. A 15-minute detour from the highway and you’ve experienced some cave art.

Cueva Ratón

You can drive to others, like one behind the old mission San Fernando de Velicatả but most are not so near the main highway. Probably the most outstanding art you can drive to is Cueva Ratón, up in the Sierra San Francisco. The little community of San Francisco is also the take-off point for mule explorations into the major cave sites where tour groups depart into the canyons.

To get there, from Highway 1 about halfway between Vizcaino and the picturesque village of San Ignacio, take the graded dirt road marked “Cuevas Rupuestas” off to the east.

The 23-mile road begins wide and straight, and then winds up a ridge to a plateau, following the crest of a mountain spur. The incredible panorama extends way out across the Vizcaino Desert to Guerrero Negro.

The road narrows and skirts cliffs bending around a deep canyon as you approach San Francisco. Way down below palm trees and pools seem dwarfed by the deep, sheer canyon walls. More remarkable, you can see the mule trail heading down into that abyss.

You actually pass the marked Cueva Ratón 1½ miles before entering town, but need permission to visit it. Small herds of goats with tinkling bells and a few lazy cows welcomed my entrance to the dusty village atop a barren plateau. I imagined it could be a harsh windy place in winter.

An old cowboy sat by a building near some tethered burros and children playing. He pointed out the house of the government coordinator, Enrigue Arce of the ubiquitous Arce family. I signed his book and asked for a guide. So, Enrique sent his brother-in-law Jorge Guadalupe Arce, a younger, leathered cowboy.

I drove Jorge back to the Cueva Ratón where he unlocked the gate and we climbed the few stairs put in by the government when they fenced the cave in the mid-1990’s. Signs explaining the paintings and viewing platforms extend the length of it.

The paintings are massive, with details of deer, cougars and hunters. Much of the black and red drawings are covered over by newer paintings and sometimes it takes a few minutes to figure out just what is what. But the awesome site gives one a feeling of intruding on a long-forgotten culture.

For those who wish to view the Cueva Ratón, be sure to register with the coordinator. It only costs a few pesos for the guide. The 23 miles to San Francisco takes about 1½ hours each way. Or you might just go on into San Ignacio and inquire about a guided trip. Or if you can, take the burro excursion to the most significant sites.

Canyon de Trinidad, Mulegé

Farther to the south, in the mountains west of Mulegé, are several cave paintings notably in the Cañon de Trinidad. Mulegé hotels can hook you up with a local guide, Salvador Castro or Ciro Cuesta to name two. Back in 2000, I set off one Sunday morning while unsettling rain clouds lingered on the mountaintops.

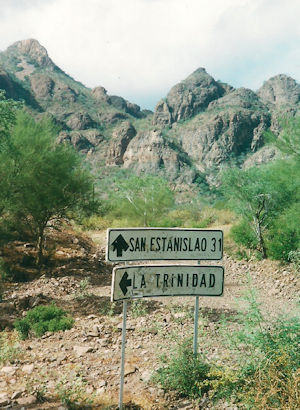

I followed a good graded dirt road through suburbs of the tropical village of Mulegé, past palm groves, farms, orchards and ranches, up through desert into the mountains on a marked road to San Eustancio. Just past a compact little rancho turn left at a small sign to “Rancho Trinidad.”

That last mile or so of the 17-mile journey from town is rougher and requires high clearance vehicles. There is one cattle gate which you must open and then close behind you. Soon you arrive at a rustic rancho on a bluff with a magnificent view to the south, from a verdant valley to steep mountains. In every direction are high rocky peaks dappled with green and white palo blanco trees perched on improbable overhangs and looking like white-stemmed bunches of broccoli clinging tenaciously to steep hillsides.

Rancho Trinidad at road’s end has plenty of water, including a large cistern you could swim in, numerous trees and cattle. It is owned by a Santa Rosalía doctor and managed by Placido Castro and his wife Armida Arce de Castro who raised four children during the 22 years they’ve been there.

I signed the official register, paid the minimal fee, and set off afoot with Placido. There are two cave painting sites in the Cañon de Trinidad behind the rancho, one is about a 1½-mile round-trip on a good trail with some boulder hopping, and the other is about a three-hour round-trip from the rancho.

Heading for the closer site, we crossed a makeshift dam and numerous pools of water. The steep canyon walls speckled with greenery gave the place an ethereal look, like a set out of a “Lost Horizon” movie. Rounding a bend, we came to a cave the early people had obviously used for lodging. Across the creek, a couple of locations offered some outstanding examples of cave art.

The murals included outlines of hands and many animals, including fish, deer and smaller game. One scene looked like a stag mounting a doe, denoting the early people’s attention to animal husbandry. There was a hunter dancing in jubilation over the slain deer at his feet. There were even arrows protruding from a human figure reminding current viewers of man’s affinity for warfare.

On the trail back and around the rancho are other reminders of early man’s time spent in the area. There are several wonderful petroglyphs etched into boulders, and metates used for grinding grain.

Armida had been busy in her detached and open kitchen while we were gone. In true Baja hospitality, she offered me some machaca (dried beef). Imagine the contrast with stepping out of the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art and being accosted by a vendor of over-priced hot dogs.

Forget the Louvre, the Prado, the Getty or the Met. The cave paintings of Baja California are wonderfully displayed in nature’s own magnificent art gallery.

About Greg

Greg Niemann, a long-time Baja writer, is the author of Baja Fever, Baja Legends, Palm Springs Legends, Las Vegas Legends, and Big Brown: The Untold Story of UPS. Visit www.gregniemann.com.