|  |

By David Kier

Baja California is a land filled with history and mystery. The location of where Spanish explorer Melchior Díaz is buried is one of the earliest North American mysteries with a Baja connection.

Following the discovery of California by Fortún Jiménez in 1533, the Spanish explored the length of the Gulf of California with the voyages of Francisco de Ulloa in 1539 and Hernado de Alarcón, the next year. Both expeditions proved California was a peninsula, despite that fact, many were unconvinced for the next 200 years and continued to view California as an island.

In May of 1540, Hernando de Alarcón left Acapulco, to support the great expedition led by Francisco Vázquez de Coronado. Coronado was seeking the ‘Seven Cities of Cíbola’ to the north of Mexico. Alarcón was bringing supplies for Coronado when he discovered the Colorado River, but he never connected with the Coronado expedition.

Alarcón may not have set foot on the California side of the river, but he and his men traveled up the river many miles in small boats. After waiting a pre-arranged time for Coronado, Alarcón returned to his ships at the head of the gulf, but left letters at a large tree and knew the natives would direct any Spaniards to it.

Marching west from the Coronado expedition to meet Alarcón was Melchior Díaz, with many Indian guides, and his troops. Díaz missed Alarcón by just days but found the message left in a jar at the base of the tree. The news from Alarcón released Díaz from his duty to retrieve supplies for Coronado. That allowed Melchior Díaz to explore the new land, west of the river. Díaz named the river ‘Firebrand’ noticing how the Indians kept warm with glowing sticks that December of 1540. The sticks were like fire heated branding irons. Díaz crossed the river using rafts, and he would be the first European land traveler to enter California. Díaz was injured in a freak accident and he died several days later, January 8, 1541. Where he was buried remains a mystery.

The story about Melchior Díaz was told by Pedro de Castañeda de Nájera in his book ‘Narrative of the Coronado Expedition’: After entering California, the Díaz expedition encountered the boiling mud pots on the west side of the Colorado Delta, later called Volcano Lake. This is at the base of Cerro Prieto volcano, 20 miles south of today’s city of Mexicali. On the fourth day on the California side of the river, Captain Díaz suffered the mortal injury. A greyhound belonging to one of the Spaniards was annoying the flock of sheep they had along for food. Captain Díaz chased the dog on horseback and threw his lance at the animal. The lance missed the dog and stuck in the sand. Unable to turn his horse soon enough to avoid running over it, the lance pierced Melchior’s thigh and bladder.

Castañeda says the men returned across the river and that Melchior Díaz lived for twenty days on the return trip. While most believed his men returned across the Colorado River with Díaz, there are some who think the men followed the coastline south, trying to reach Alarcón’s ships. It is this possibility that sparked a light in the mind of desert explorer Walter Henderson when he read the story of Melchior Díaz. During the depression of the 1930’s, Henderson and a companion traveled south of Mexicali seeking the exotic blue palm trees of the canyons of Baja California. He heard from a prospector that some were in the Sierra de Las Tinajas and Sierra de La Palmita. These two small desert mountain ranges are about 70 miles south of the Mexicali border and 20 miles west of the road to San Felipe.

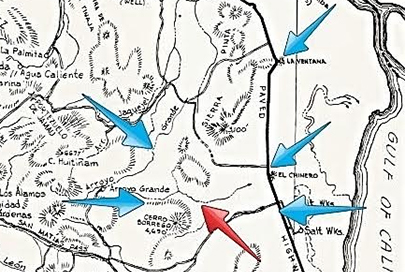

Henderson writes that they left the San Felipe road about 20 miles south of La Ventana and traveled west to the base of the Sierra Pinta, as far as his Model A Ford would take them. The next morning they traveled into the hills, using the most obvious of routes to reach the Sierra de Las Tinajas. They would discover that they began their hike too far south to reach that mountain, within the limits of their time and water supply. They reached the top of the Sierra Pinta range and then went steeply down the west side, into Arroyo Grande. Around noon, roughly 1/4 to 1/3 of the distance down from the divide, Henderson says they came upon a large and very unnatural looking pile of rocks. It was on the north side ledge of the rocky ravine. No sign of any human presence, such as wood cutters or prospectors was near here, so it seemed most odd. The rocks were coated with desert varnish, indicating they were placed many, many years or even centuries ago.

They made camp that night in Arroyo Grande, and returned the next day to the Model A by traveling up Arroyo Grande to the base of Borrego Mountain and then back east to the car. Years later, Walter read about Melchior Díaz and the lost grave. This Spanish captain was a highly respected man and would have been buried with his possessions. Walter Henderson believed his rock pile could be the missing grave and made several attempts to have the Mexican government follow his route and protect or extract the remains for their great historic value. The answer he got was that he would have to finance the expedition if he wanted Mexico to save the treasure and put it in a museum! Not a remote chance of that happening and so Melchior Díaz, or perhaps just a ‘pile of rocks’ remains to be rediscovered.

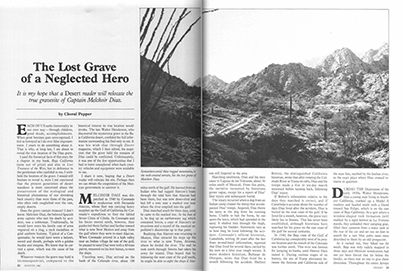

Many years later, writer Choral Pepper shared Henderson's story in her 1973 Baja California book after he sent her a letter about the finding. Henderson provided details and directions to a ‘rock pile’ he found in Baja. Since Mrs. Pepper was the editor of Desert Magazine he thought she could be a great outlet for sharing the discovery with fellow desert enthusiasts who might have an opportunity to find the possible 1541 grave site. The story was featured in the August, 1981 edition of Desert Magazine, but this time with more location details. It was from this magazine story that excited San Felipe desert explorer Bruce Barber who spent a great amount of energy analyzing Pepper’s story using science, and searched the desert hills north of San Felipe. The problem is that Pepper’s 1981 story gave an incorrect starting point for Henderson’s hike. I know because I have the original 1967 letter Walter wrote to Choral. I have since shared the letter with Bruce Barber, who had so much passion for finding the Díaz grave and devoted much of his 2003 book “...of Sea and Sand” to the search.

Choral Pepper passed away in 2002 and wanted me to continue my sharing of the Baja history that is so exciting to many, so she instructed her family to leave her Desert magazine Baja related photos and letters to me. In 2009, I found her ‘Lost Mission’ of Santa María Magdalena. In 2015, I hoped to find the other mystery that remained: the rock pile location.

The following are critical notes from Walter's letter to Choral Pepper:

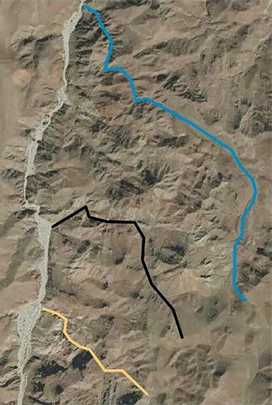

In April of 2015, four friends (Tom, Joe, Karl, Harald) and I camped in Arroyo Grande and explored 3 possible canyons coming down the Sierra Pinta. It was about 10 miles from the Model A parking spot to the divide. Arroyo B (blue line) is 3 miles long. The middle canyon (black line) I named ‘Arroyo A’ and a small dam at its entrance required a detour climb around to enter the lower region. Beyond there were just a choice of narrow gullies blocked by boulders. Two of our group climbed up to the top of the canyon ridge but found no clear arroyo path higher. The south canyon (yellow line) was named ‘Arroyo D’ in my pre-trip planning. We could actually drive up it for some distance before beginning the hike. That promising feature soon ended as the canyon narrowed and got steep. A surprise was finding a large cave and made the hike that much more interesting. The north canyon (black line) is my ‘Arroyo B’, and was my first choice to explore. However, a week prior to our trip, another friend (Paul) discovered an impassable dry waterfall making it unlikely for Henderson or the Díaz Party to have used it. Paul hiked into Arroyo B from Arroyo C, which ends in Arroyo Grande, further north.

Sadly for us, all three routes up from Arroyo Grande had rock obstructions that made getting to the divide seemingly impossible. No way could horses and a man on a stretcher pass, unless the canyons were far different than today. A helicopter would seem to be the best way to find the rock pile!

The 1930’s rock pile found by Walter Henderson and the 1541 grave of Melchior Díaz remain to be found somewhere in the desert of Mexico. Should you have the good fortune to find them, this author (and many other history buffs) would be very happy to hear from you!

About David

David Kier is a veteran Baja traveler and the co-author of 'The Old Missions of Baja and Alta California 1697-1834. Visit The Old Missions website.