|  |

By David Kier

San Bruno was the site of a fort and colony established by Admiral Isidoro de Atondo y Antillón and Padre Eusebio Francisco Kino. They are the oldest ruins in Baja or Alta California.

San Bruno, however, was not the first attempt to colonize California. Cortés tried in 1535 and Vizcaíno tried in 1596. In April 1683, the Atondo/ Kino party first arrived at La Paz and there they built a base of operations under the name Real de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe. Three ships were in the service of the new colony, the Capitana, the Almiranta, and the Balandra. The Balandra, which had suffered difficulties did not arrive at La Paz until after the colony was abandoned. Besides the difficulty with supplies, tensions were rising with the Natives. Skirmishes were increasing and these altercations came to a head on July 3, 1683. Admiral Atondo ordered their cannon fired upon the Natives whom had come into the compound to enjoy a meal. Of the sixteen Natives seated, three were killed. On July 14, the colonists abandoned La Paz and returned to the Mexican mainland.

Two months were spent refitting and resupplying the endeavor before Padre Kino on the Almiranta and Admiral Atondo with Padre Goñi on the Capitana, sailed for California once again. They crossed with 177 soldiers, 38 civilian recruits, and 50 young horses. They arrived at the beach of San Bruno on October 5, 1683. Padre Kino, with Atondo and a few soldiers traveled about 2 miles up the arroyo to a village. The water here was good and Atondo noticed an elevated site nearby that looked appropriate to make a secure camp.

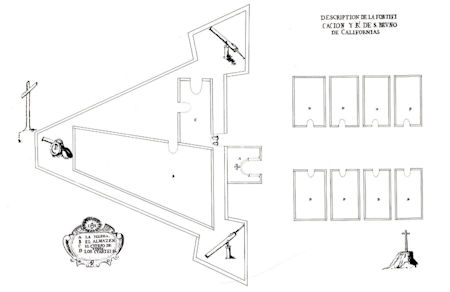

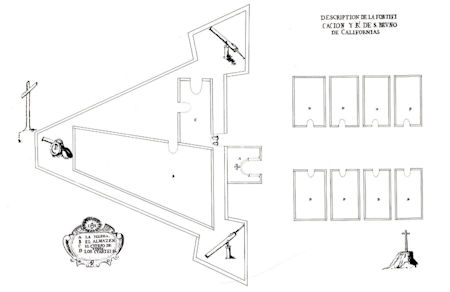

Less than a week later, the stream which they named the Rio Grande, no longer flowed. Water would come from wells dug in the arroyo. Kino wrote, “Such are California rivers – they sometimes have water.” On October 10, 1683, a large cross was brought up the hill. Temporary quarters were made on the flat below the little mesa. On October 28, the Real de San Bruno was established and a triangular-shaped fort with three cannon points constructed. Until Padre Kino was certain this colony would succeed, he would refrain from baptizing very many Natives. His fear being if the Spanish abandoned the site there would be no priest to serve the converts or provide services and instruction in the Faith.

Atondo named this region of California, San Andrés, and took formal possession of it on November 30 for the King of Spain. The next day, Atondo, Kino, and 25 soldiers with 18 Natives made a 12-day expedition to explore the region. Three leagues (about 6 miles) up the arroyo, they found water and pasture. They named the location San Isidro, but Natives here called the place Londó. Londó would be a very productive location and was a farming station of San Bruno. Sixteen years later, San Juan Londó became a visiting station of Loreto. Ruins of the church at Londó are visible today, just west of Highway 1, at Km. 30. Kino found other possible mission sites as he traveled further to the northwest.

The colony seemed to be successful for most of 1684 and relations with the Natives was generally good. The lack of good water at San Bruno was perhaps the greatest drawback to a colony there. In August of 1684, the Almiranta brought new supplies and another Jesuit, Padre Juan Bautista Copart, to the colony. On December 14, after four successful sea crossings to California, the Almiranta needed repairs and sailed for Matanchel.

The greatest expedition for the colonists was when Kino and Atondo crossed the peninsula to the Pacific Ocean, in 1684. They began from San Bruno on December 14 and arrived at the Pacific on December 30. The seashells Kino saw (blue abalone) would have a huge impact on his discovering that California was not an island. During the years that followed, when Kino worked in the regions of Sonora and Arizona, Pima Indians in Arizona had traded with Indians from the Pacific and had the same blue shells. A shell not found in the Gulf of California.

Lack of good drinking water and insufficient supplies from the mainland caused outbreaks of scurvy and finally, on May 6, 1685, the fort was dismantled, packed, and put on board the Balandra and Capitana for the return to the mainland. Even though the colonies at La Paz and San Bruno both failed, what Kino learned from the experiences there would make the Jesuits next attempt succeed. Sadly, Kino could not return to California as planned. He was to go with his friend Padre Salvatierra in 1697 for the founding of Loreto, just 15 miles south of San Bruno. Kino’s superiors needed him to remain on the mainland to deal with potential Indian issues there. Kino would later travel to the area of Yuma, Arizona, and cross the Colorado River, proving California was not an island.

To reach San Bruno, a 4WD vehicle is needed followed by a short hike up the hillside from the arroyo. Turn east on the road at the south side of the bridge at Km. 26. Go into the big arroyo and follow it east, past sand mine pits. In 2.5 miles, the arroyo curves and note a road going across the arroyo. Turn on it to the north. Take it 1.1 miles, across another arroyo. Go to the right about 200 yards to the base of the hill with the ruins. A trail goes up to the site: N26°13.960', W111°23.900'. Locals say that cut-stone blocks were hauled away from here many years ago to be used at a home in Loreto. There is very little to see today, but the ruins from 336 years ago make visiting this spot quite a step, back in time.

Update: In 2022, satellite imagery showed a road was built up to the site. It was cleared and leveled, and the ancient walls were demolished and restacked to simulate the fort outline.

About David

David Kier is a veteran Baja traveler, author of 'Baja California - Land Of Missions' and co-author of 'Old Missions of the Californias'. Visit the Old Missions website.