|  |

By David Kier

Maps courtesy of 'The King's Highway in Baja California' by Harry Crosby.

In the Californias, El Camino Real was a road for people and pack animals that connected the missions with each other and was the line of supply and communication for over two hundred years.

A cuesta is a road grade, and on El Camino Real in Baja California it is one that is typically steep with switchbacks cut into the mountainside so pack animals and people could travel up and down the peninsula where mountains would otherwise force long detours.

The Jesuit missionaries who operated the missions from 1697 to the end of 1767 engineered the road network between their missions to a high degree, in the name of the king. The Royal Road of California began in Loreto and radiated out to the missions and visitas (satellite mission outposts) established on the peninsula. These roads can still be seen for hundreds of miles where modern construction or natural erosion has not obliterated them.

Howard Gulick in the 1950s and Harry Crosby in the 1970s documented the Camino Real across much of Baja California. Their notes and maps help us find the ancient ‘highway’ in the twenty-first century, both on land and from space with the satellite map images available.

The Jesuit’s Camino Real usually ran in straight lines for long distances when the terrain permitted. At canyons or mountain passes are when the cuesta switchbacks would be employed to cross those obstacles.

There was often more than one Camino Real between many of the missions. Conditions would force a different route to be used, often for available water sources, or to visit one of the satellite mission stations (visitas) enroute. The most documented route of El Camino Real is the one used by Junípero Serra on his 1769 expedition from Loreto to San Diego Bay.

Two land expeditions set out from Loreto that year. The first was led by Captain Fernando de Rivera and Padre Juan Crespí. Crespí was the missionary at La Purísima until his journey north began in February of 1769 and with Rivera, they traveled to the edge of the Jesuit’s influence which was at Velicatá. Three years earlier, Padre Wenceslao Link had found Velicatá was an excellent site for a mission. The Jesuits were removed from all Spanish territory before they could establish a mission that far north. Crespí and Rivera arrived at Velicatá in March of 1769.

Junípero Serra with Captain Gaspar de Portolá, the newly appointed governor of the Californias, began their journey two months after Crespí and Rivera had started. When Junípero Serra arrived at Velicatá in May of 1769, he concluded it was indeed such an important location that it became his first founded California mission, and he named it San Fernando.

Padre Crespí documented the trail in great detail and that helped modern explorers like Harry Crosby discover the route used for his preparation of the two books, The King’s Highway in Baja California (1974) and Gateway to Alta California (2003).

Creating a trail for mules to bring people and cargo began early for the Jesuits when they expanded from Loreto to their second mission of San Javier. The canyon between the two sites required roadbuilding and at first the soldiers were employed. It didn’t take long for the Spaniards to utilize the large Indian workforce that was available for such tasks and a road was carved into the canyon walls to reach the valley above. That cuesta was near Las Parras, where wild grapes grew. The San Javier mission was first established in 1699 at today’s Rancho Viejo and moved south five miles after about ten years.

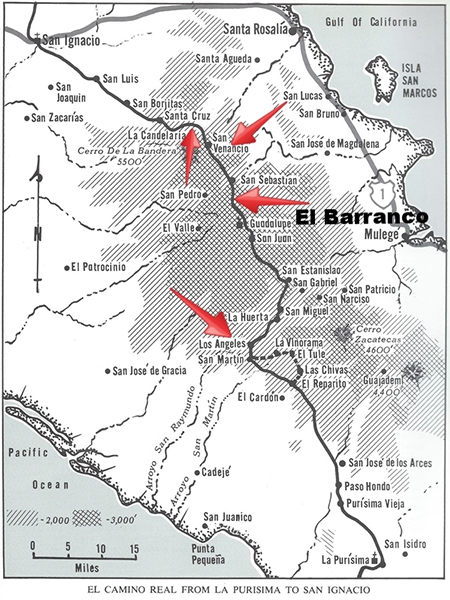

Perhaps the next major cuesta is found northbound between La Purísima and Guadalupe missions. Called Cuesta de los Angeles, this grade drops the Camino Real into Arroyo San Raymundo a few miles downstream from the mission visita of San Miguel. The topo map shows a ranch named Piedra de la Cuesta (Stone of the Grade) on the bottom of the grade. According to Harry Crosby’s book, the ranch is called Pie de la Cuesta (Foot of the Grade). GPS at the top of the grade is 26⁰39.825’, -112⁰20.900’ (1,640’). These cuestas and much of the mission road system can be seen on Internet satellite maps.

The next cuesta is north of Mission Guadalupe on the way to San Sebastián and is called El Barranco. 26⁰57.250', -112⁰ 25.090' (3,280’). Before auto roads were constructed in the 1980s, a mule was needed to visit the mission over this trail.

From San Sebastián the mission road passes through El Gato to the Cuesta de San Venancio. 27⁰04.470’, -112⁰28.770’ (3,100’). The trail follows the ridgeline about a mile west before dropping steeply down and passing near La Higuera and coming to La Candelaria. The next steep grade was just beyond Rancho la Candelaria and is known as Cuesta La Candelaria 27⁰ 05.920’, -112⁰ 32.690’ (3,225’) which brought the road onto the plain leading to San Ignacio. The Camino Real continues to San Ignacio, passing by the ranchos of Santa Cruz and San Luis.

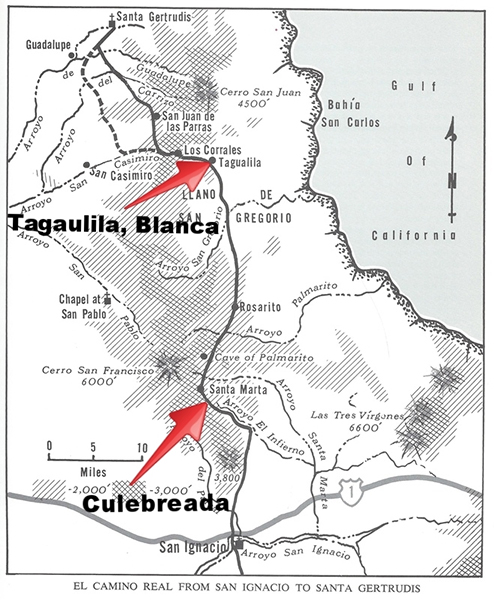

The region between the missions of San Ignacio and Santa Gertrudis by far has the greatest number of mission roads that can be seen today. The area is remote and rugged. San Ignacio’s Padre Consag was very ambitious to expand the Jesuit missions to the north and may have initiated the many road construction projects out from San Ignacio. From the air (or satellites in space), one can see many roads radiating out from San Ignacio like spokes of a wagon wheel. There were basically three Jesuit El Camino Reals on the peninsula (Pacifico, Sierra, Golfo) based on the location of them on the peninsula.

A cuesta culebreada (switchback grade) as Harry Crosby called it, is between Arroyo el Infierno and Santa Marta, located at 27⁰29.800’, -112⁰55.830’ (2,600’). Cuesta de Tagualila at 27⁰49.777’, -113⁰01.300’ (1,840’) is where the Camino Real leaves the San Gregorio Plain and Crosby noted that here the old road is very deeply built with loose rock as much as five feet high on each side. Near the bottom of this grade, another branch of the Camino Real is seen as it climbs a short, steep grade. The cut trail is colored white compared to the dark volcanic surface rock. The top of this “Cuesta Blanca” is the small lakebed, Laguna la Tahualina. Both branches come together again several miles to the northwest.

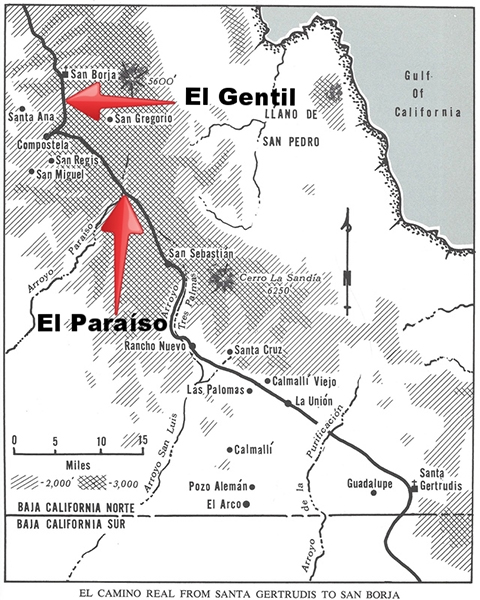

Mission Santa Gertrudis was founded in 1752 at the only water source available for farming and ranching activities as needed for a colony in the desert. The multiple Camino Real roads converge at or near this mission. Heading north for San Borja, we can see a choice of roads available to the people of the time. The primary route is the Sierra Camino Real and heads northwest from Santa Gertrudis, like an arrow shot in as straight a line, as much as the terrain would allow, for nearly half the distance to San Borja. The mountains and the deep canyon of El Paraíso would be the barriers to the mission road alignment.

The Paraíso Canyon was a 1,200’ plunge for El Camino Real that began at 28⁰31.560’, -113⁰38.220’ (3,400’) and then a climb back out 2.3 miles up the canyon, past a ranch that began as a mission farm for San Borja, in the 1760s. Just two miles beyond the north rim of the canyon, El Camino Real comes to Las Cabras where the Spanish first saw snow in California, at an elevation of 4,000 feet.

The final switchback cuesta before reaching Mission San Borja is called El Gentil, named after the plain between it and San Borja. The name Gentiles (along with heathens, pagans, and savages) was used by some of the missionaries and Spanish soldiers to describe the natives before they had become neophytes (baptized members of the mission).

The wonderfully preserved road construction that can be seen for much of the distance north from Loreto comes to an end at San Borja. The Jesuits were removed by force from all of the Spanish New World and replaced in California by the Franciscans, led by Junípero Serra. The short time following the founding of the final Jesuit mission (first at Calamajué then moved to Santa María) and the expulsion did not allow for the typical Jesuit road construction. North of San Borja, El Camino Real resembles not much more than a cattle trail. Some construction can be seen near Mission Santa María made by the Franciscans to facilitate their 1769 construction and development of Santa María and San Fernando de Velicatá.

Find the old Camino Real and if you can, take a walk along it to get a sense of what it was like to travel in Baja California over 250 years ago.

About David

David Kier is a veteran Baja traveler and the co-author of 'The Old Missions of Baja and Alta California: 1697-1834. David Kier’s research on the twenty-seven missions of Baja California was recently published in a new comprehensive book. Visit The Old Missions website for additional information.